| Mon

Book Info

Subscribe

| |||

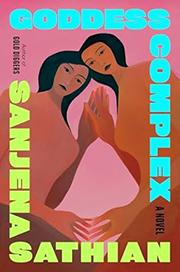

Dear Reader, There's an art to telling a story in 350 to 450 words (the ideal number to use in my daily column). But what if you had to tell a story using only one word? Which got me to thinking, if I had to describe myself in one word, what would that word be? How about you? What one word would best describe who you are? Settle back in your chair, because it's a tough question to answer quickly. I thought about it all night long and finally I decided on the word--approachable. I want people to feel joyful and at ease around me. If someone needs help, I want them to feel comfortable asking me. I emailed some friends and folks on staff asking the, "What one word would best describe you?" question. Only I didn't give them an overnight to answer. I was a bit of a fiend because I included a little note indicating I was on deadline, so could they answer right away? I was surprised at how quickly one reply showed up in my box, "Wow. Nothing like a hard question before my morning coffee. I guess it would be devoted or faithful." While I was waiting for more replies I asked my husband the one-word question. A painful look came over his face, as he was shaking his head he didn't know. So I've answered the question for him. If I picked one word to describe him it would be--superman. Another staff person replied, "Suzanne, I couldn't think of a word, my mind went blank, so I called and asked my husband. He said, devoted." But 15 minutes later she changed her mind and decided on, approachable. (Maybe there is a reason we all work well together.) So if you had to tell a story about yourself in one word, what would it be? I'm curious. Thanks for reading with me. It's so good to read with friends. Suzanne Beecher P. S. This week we're giving away 10 copies of the book Goddess Complex: A Novel by Sanjena Sathian. Click here to enter for your chance to win. | |||

Goddess Complex: A Novel | |||

Expectations It began innocuously enough, with a text message from an unknown number that arrived while I was soaping my armpits in the ladies' room of the New Haven train station. SO YOU AND K ARE BACK IN TOWN I presumed that the sender had seen me lugging a forlorn expression around campus recently, where I was, in fact, back after a long spell away. Possibly we had even brushed past each other on the train platform moments earlier. I glanced over my shoulder, quickly, as if some figure might materialize from one of the Pepto Bismol-pink toilet stalls. Then I stood, very still, for perhaps half a minute. All was silent. I became suddenly aware of the foolishness of my posture, the way I was leaning toward the mirror, lit by the sickly fluorescence, my true eyes fixed on my reflected eyes, like a cat tensing up at its likeness in a windowpane. I shook off the chill that had run down my neck at the sight of the initial, K. There had been nasty, disjointed flashes like this all year, as acquaintances whose names I could not remember, whose faces I failed to place, crossed streets or cafés to say hello and, inevitably, ask about Killian. He was, after all, still legally my husband. I usually just said, "Oh, he's out of town," because I could not bring myself to explain the limbo of our situation. I had ghosted him last summer, and we had not spoken in nearly a year. I was something between a wife and an ex-wife, between who I had been and who I would be next. I pocketed my phone and returned to the task at hand: dabbing my smelly underarms with a damp paper towel. I had stopped shaving (out of laziness rather than self-empowerment) and the more forested my pits grew, the more they seemed to become their own ecological zones. On top of that, I had lost my deodorant, and I could not bathe, as I could not go home: it was commencement weekend on campus, and in order to escape the celebratory crowds of smug families and promising graduates who would emphasize, by contrast, my own pompless circumstances, I'd Airbnb'd my place to some undergrad's parents and fled to my friend Lia's, in Brooklyn. My stay had begun pleasantly, until, after I'd poured the four dollar wine I'd brought as my keep, Lia coyly pushed her glass aside and announced that she was expecting. "Expecting what?" I asked, absently, thinking of a piece of mail, or another guest. "Expecting expecting." Her beam matched the sheen of her stainless-steel appliances. Lia and her husband Gor had recently bought a two-bedroom condo in a new construction high rise in Dumbo. All the appliances seemed straight out of plastic wrap. I felt like a mannequin in a showroom. In college, Lia had passed one barefoot, braless summer volunteering on a dairy farm, sleeping on alpaca rugs, extolling Diva Cups. More recently, she and Gor, both attorneys at white shoe law firms, had been featured in a New York magazine piece about millennials' homebuying "journeys." I was still unaccustomed to this new Lia, who had found serenity in her renunciation of renunciation. My throat clogged, and instead of congratulating her on having become successfully inseminated, I said, "Who the fuck says expecting instead of pregnant?" Her doll-like features immediately contorted into an expression of utmost sympathy. I grasped that she thought I was jealous. It was true that my life was increasingly becoming the warped inverse of hers. I'd left Killian the month she and Gor celebrated their two-year wedding anniversary; signed a lease on a dank studio weeks before they closed on the condo. And there was something else, too: unbeknownst to Lia, I had terminated a pregnancy last August. The pregnancy had transformed what had once been my ambivalence about childbearing into a certainty. I could only think: I do not want it in me; I cannot be split. For weeks after the procedure, I cramped and bled. The doctor said the bleeding went on too long; my womb, she deadpanned, had "relaxed too much." So, no, I did not envy Lia's forthcoming rascal. If I coveted anything about her life, it was the glow of comprehensibility that surrounded her. Once, I, too, had made sense, but of late, I was becoming less defined. I seemed to have abdicated my birthright citizenship to the nation of marriage and mortgage and motherhood, and beyond its borders lay uncharted terrain. I did mourn something after the procedure—not a specifically rendered unborn child, some slo-mo picture of a dark-haired creature soaring higher and higher on a bright red swing. (I had not contracted Killian's childhood Catholicism.) Rather, I grieved the loss of a version of me who was more fathomable to the world. Had I told Lia about the abortion, she would no doubt have glanced, pro forma, at the pink i'm with her mug on her trinket shelf, assuring me (assuring herself) that she bore no judgment. But I feared that everyone I knew had suddenly inherited a capacity for love that I lacked, and I was certain they believed that I was missing out on the Fundamental Mystery of Humankind. So, I kept my choice to myself. I tried again: "Wow!" I said. "Your baby will be so cute." Lia bit her lip. I asked whether she and Gor planned to hyphenate Wojciechowski Grigoryan. Her palm flattened against the gleaming black countertop like she was massacring a large bug. "I guess I never told you. I took his name." She stood abruptly and went to dump her wine in the sink. With her back to me, she began to loop a lock of her blond hair around her index finger, turning the knuckle paperwhite, cutting off circulation. She was nervous. "No. Or, yes," I agreed. "You never told me." "I knew what you would say." Her vast blue eyes narrowed warningly, puddles shrinking in the sun. "And before you say it, there are a lot of reasons people change their names." Lia enumerated them: being closer, forming a clear family unit. Anyway, what was feminist about being forced to choose between her shitty father's unpronounceable surname and her very nice husband's? I pointed out that my name is Sanjana Satyananda and Killian's is Killian Bane, but I had not become Sanjana Bane in order to assimilate into an easier identity. Plus, I added, she was blond. She asked what that had to do with anything, and I said it meant she didn't get to complain about her ethnic last name. Things escalated from there, and in the end, discovering that my dearest, oldest friend had remade her legal identity without informing me led me to snark something half-baked about the ethics of reproducing in the face of climate change. Lia burst into tears, which, while not unheard of in our eighteen years of friendship, made me seem especially cruel now that she was crying for two. Gor soon appeared in the doorway and suggested I leave. I am an anthropologist, so I know: spinsters make good demons. We infiltrate the bodies and minds of the happily married, sowing discord. We steal babies, kill babies, eat babies. You have to banish us. Out in the field, I knew a female healer who specialized in exorcisms for infertile women. Her instrument of choice was the broomstick, with which she beat barren wives. The wives themselves sought this treatment. Often, they came to the healer knowing exactly what, or who, was to blame for their empty wombs, and they'd tell the healer: My sister, my neighbor, my enemy, she died unfulfilled (which could only mean sonless) and cursed me with this brutal bequest. Then the healer would lift her broom and get to work delivering the blessing of progeny. (continued on Tuesday) Love this book? Share your review with the Publisher

| |||

| Mon Book Info | |||