| Mon

Book Info

Subscribe

| |||

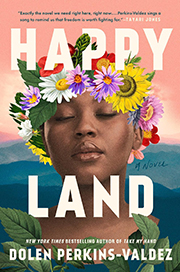

Dear Reader, One of the things I have to keep in check is that sometimes I think other people should do things my way. My way might be the perfect way for me, but it's not necessarily the right way for somebody else and whenever I need a reminder, I think of my Aunt Florence. I love my aunt dearly, but most people describe her as an overemotional and dramatic woman because of the way she reacts to things. It's true, drama and my aunt seem to travel hand-in-hand, but most of the time it's not her fault. My aunt knows her limits, but for some reason people don't want to believe her when she tells them, "It would be better if I didn't." When my father died Aunt Florence announced that she wouldn't be able to handle going to her brother's funeral. Instead, she offered to stay at my parents' house and take care of the children and she said that if someone stopped by to drop off a casserole (like they do in small towns) that she'd be there to greet them. It was a job that someone needed to do and it made her feel good to know that she'd be doing something in honor of her brother. "But you'll regret it later," the relatives told Aunt Florence. "You have to go to the funeral, it wouldn't be right for you to miss the service." Florence tried her best to make them understand, but everyone insisted that at least before the casket was closed, she needed to see her brother one last time to say goodbye. So my aunt finally agreed and she did go to the funeral home. But shortly after she arrived my aunt collapsed, and they had to call an ambulance. "Oh, you know Florence," the relatives were commenting, "there she goes again being all emotional." But the truth is they didn't know Florence. She knew the best way for her to honor her brother, but they had their own ideas and refused to listen. Thanks for reading with me. It's so good to read with friends. Suzanne Beecher P. S. This week we're giving away 10 copies of the book Happy Land: A Novel by Dolen Perkins-Valdez. Click here to enter for your chance to win. | |||

Happy Land: A Novel | |||

|

ONE Nikki The only thing I know about my grandmother's home is that it's in an isolated area of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Zirconia, North Carolina. And the only thing I know about Zirconia is that it's right outside Hendersonville. And what I know about Hendersonville is that it has a lot of apple orchards. A shame, I know. The old 25 highway is two lanes without a line in the middle. I pass a wood-frame house that must be at least a hundred years old, a neat and tidy brick rambler with rockers lining the front porch. Stuffed fairies hang from tree limbs, and a motionless cat stares at me from a front yard. I wind the rental car around a series of camp entrances. Camp Greystone. Camp Arrowhead. Houses on tall wooden piles perch around a sign labeled LAKE SUMMIT. Just a few miles past the lake, I pass the granite cliff Mother Rita mentioned over the phone, and just after that I reach the entrance to her property. Lovejoy Lane. When I was born, I was given my mama's maiden name hyphenated with Daddy's name—Lovejoy-Berry—in a gesture I'd always attributed to Mama's feminist pride. When I married Darius, I didn't change it. So seeing that Lovejoy sign does something to me. It looks official, as if the county provided it. I've never seen it before. I'm almost forty years old, and this is my first time ever visiting my grandmother. As I turn into the dirt drive I wonder how long my family has lived in this house. The siding is in need of a paint job, and the green shutters are faded and weather-beaten. I know Mama grew up here, and as I note its wide front porch and gabled roof, I imagine her, an only child, running down the front steps. It's morning, but the porch lamp is on, moth carcasses stuck to its dimly lit dome. I can't find a doorbell. I hesitate, then knock softly on the frame of the wooden screen door. A couple of minutes pass before I knock again. Maybe she's asleep. The elderly do tend to keep their own hours. Finally, the door opens and a tall lady with a shock of gray hair peers through the screen at me. "Yes?" "Mother Rita?" I've always called her that, following Mama's lead. "Veronica? I was expecting you later this evening." "I'm sorry. They offered me a travel voucher, so I took a morning flight instead. I should have called." "Yes, you should have." She pats her hair down. Inside, the house is well kept—brighter and airier than I expected considering the condition of the exterior. Actually, I'm not sure what I expected, perhaps a dusty house filled with relics that haven't been moved in years. Instead, the rooms are sunny, cheerful. I spy a settee too delicate for sitting in the living room, a tarnished silver tea set on a sideboard in the dining room, a Persian rug too big for the space. Everything is old, worn to the threads, but it's clean. Mother Rita wears a pair of jeans and a neat, collared shirt turned up at the elbows. Despite her unruly hair, she looks pretty, especially for seventy-eight years old. It feels like forever since I've seen her. Actually, it's been eight years. I remember because when my daddy died, Mother Rita drove all the way to D.C. for the funeral, only to turn around and drive home the next day. "You ate yet?" "Yes, ma'am," I respond politely, though the truth is that I'm starving. She glances down at the rolling suitcase I've just parked in the middle of her living room. It's as if she can see everything at once—my uncertainty, my curiosity, my fear. "Bathroom is down the hall on the left. When you've finished, I got some leftover navy beans from yesterday. I'll warm those up with a little corn bread?" She uses a questioning tone, but I know there is no need to answer. This is her extension of hospitality, and I'm grateful for it. A fuzzy pink rug covers the bathroom floor, its matching cover on the toilet seat. Behind the shower curtain, fish tiles rim the walls. Above the towel bar hangs a faded picture of a young man dangling a fish between his hands. My grandfather passed away when I was in elementary school. I lean closer to better make out his features. I wash my hands slowly, taking my time. When Mother Rita called and asked me to come, the timing wasn't great. My daughter, Shawnie, graduated high school last year and still doesn't have a full-time job. We've been fighting about it all summer. I've got a house on the market, but in the last couple of years I've lost my joy for selling real estate. I haven't sold a single property in months, and I'm about to run out of savings. If I don't get my act together, I'm going to be in real financial trouble soon. The truth of the matter is that my life is a mess right now. When I hesitated, Mother Rita was insistent—'I need your help and if you come down here I will tell you everything your mama hasn't told you about our family.' It wasn't exactly an invitation I could refuse. In the kitchen, she stands before the beans warming on the stove. I sit at the table, my eyes tracing her shoulders. I've seen Mother Rita only a handful of times in my entire life—my tenth birthday party at Crystal Skate, my high school graduation, Daddy's funeral. Even when Mother Rita did come to D.C., she and Mama were painstakingly polite, not like mother and daughter. I have always quietly believed they hated each other's guts, even before their final falling-out. All that to say that this is my first opportunity to spend time with my grandmother one-on-one without Mama's feelings running riot in the air. I want to ask her so many questions, but my tongue sticks to the roof of my mouth. Maybe after I get some food in my belly and we're seated across from one another, we can talk. "You don't have a microwave?" I ask as she stirs. "What's that, honey?" "A microwave. To warm the beans." "Oh, I don't fool with microwaves. Never have. Don't trust them." I nod, wondering what other old notions she holds. I want to get up and help her, but she doesn't seem to invite the second pair of hands. She spoons the beans into a bowl. "See, that didn't take long, did it? This fire suits me just fine." "Smells good." "I hope you don't mind the taste. I don't eat meat." "I'll eat whatever is in that bowl," I say, though I am surprised to hear this. I wonder if she has always been vegetarian and if I just never realized it on those few occasions I've seen her. I know so little about this woman. My own kinfolk. She slides a piece of foil out of the oven. The corn bread triangles are browned, edges crisped. She uses her bare fingers to drop the hot slices on the plate next to my bowl. "Eat up. There's plenty," she says. I want to talk more, but my stomach has other ideas. The beans aren't just salted. They contain something else that gives them depth, replacing the taste of a meaty bone. "That's fresh fennel from my garden. I like to put it in my beans. Make a difference, don't it?" My mouth is almost too full to respond. "It's really good. You ate already?" "Don't worry about me none. There are more beans in the pot. Your room is the second door on the left. When you finish settling, come find me. I'll be in the yard out back." I am awash in gratitude for this simple but hearty meal. I eat in silence after she leaves me. I finish eating and wash out my bowl before placing it in the empty dishwasher. Thank goodness my grandmother owns some of the other modern conveniences. The kitchen isn't large, but it's neat with an everything-in-its-proper-place kind of feel. A wellloved cast-iron skillet hangs from a nail on the wall. An oldfashioned bread box on the counter. A butcher's block of knives. The floor appears freshly swept. I am humbled by her tidiness, by the thought that this woman lives alone but keeps her house as if someone impressionable could drop by at any moment. Or maybe I'm the impressionable person. Maybe she cleaned up knowing I was coming. The thought flushes me with unexpected warmth. Mother Rita is an only child, Mama is an only child, I'm an only child, and so is my daughter, Shawnie. Granddaddy Herbert's people were from South Carolina, and he was a Jones, but Mother Rita kept the Lovejoy name and gave it to her daughter, an unusual choice for women of her generation. I'd always wondered about that. I know the Lovejoys have deep roots in the Hendersonville area, but beyond that I don't know much of the family history. Truth is, I've never been that interested in these mountains. Other than when Mama reminds me she was born and raised in Appalachia, I haven't thought about it much. To me, Appalachia is a concept. Something on television specials. Something I associate with old-time music. (continued on Tuesday) Love this book? Share your review with the Publisher

| |||

| Mon Book Info | |||